Seed Understandings for Reconciling the Inner and Outer Self

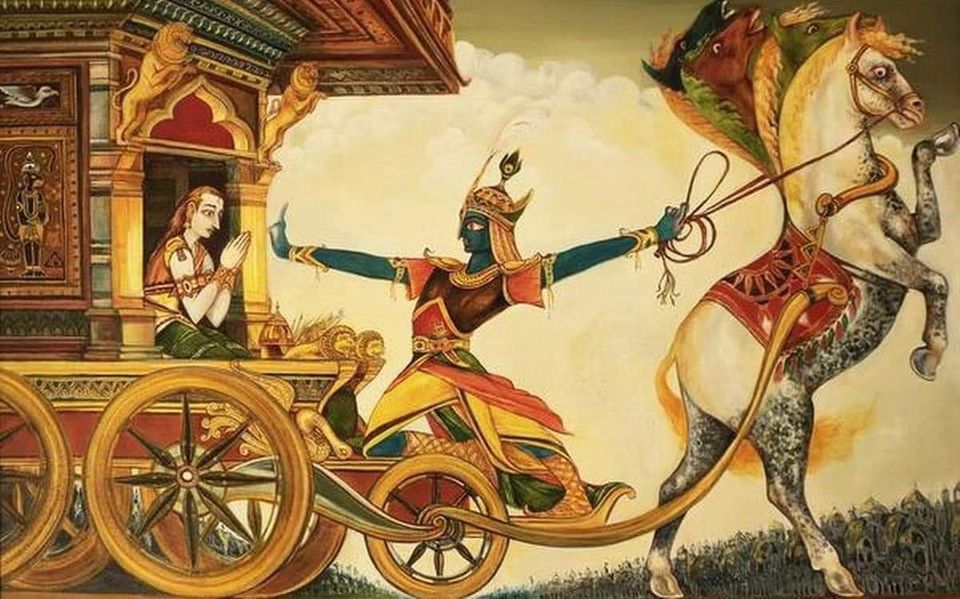

Chapter Two Gita

Passage 1 (2.1-3): Krishna responds to Arjuna’s Arguments

- Krsna responds to Arjuna’s emotionally informed argumentation with an emotionally informed rejection of his arguments as ill timed, weak hearted, not civilized and leading to infamy in this life and absence of heaven in the life hereafter

Passage 2 (2.4-10): Arjuna Comes to the Breaking Point and Surrenders

- Arjuna doubles down on his arguments demonstrating it will take more than an emotional response to bring about a change of heart

- Arjuna descends into a viscerally felt vulnerability, not based on justifying his emotions, but rather the need for reconciliation.

- He admits an inner-conflict (an obfuscating of his nature [svabhava] by karpanya [miserliness = upwelling of emotional turmoil = ignorance] and how its causing an outer conflict of confusion about what is dharma

- Inner conflict = existential dilemma

- Outer conflict = ethical dilemma

- One often leads to the other; they’re not mutually exclusive domains

- Arjuna ask for definitive instructions about what is sreyas (ultimate good/welfare [as oppose to just preyas = immediate good/welfare]) as his inner and outer conflict brings him to his knees in receptivity of higher enlightenment [2.7] denying material well being and material knowledge as viable in solving these conflicts of the heart [2.8]

- 2.7-8 again practically speaks to the tension and need of reconciliation of the inner (spiritual) and outer (social) domain of being which the Mahābhārata and Gītā’s opening chapters (2-6) seek to provide an answer (angle of vision)

Passage 3 (2.11-30): Krishna Teaches About the “Inner-Self, ”Atman (Consciousness)

- Krishna responds to Arjuna’s concern of the death of love ones by teaching about the true nature of the ātmān (individual conscious entity)

- Essentially the ātmān can’t die due to its ontological nature as different from material bodies, therefore Arjuna’s argument to avoid his dharma (of righteous killing) is null and void

- Two major ideas:

- Teaching of ātmān is to support the involvement in social world and not to inspire contraction away from it

- This passage speaks to the interior domain of being (whilst the next passage speaks to the exterior/social domain of being). Thus this passage works as an implicit introduction to the topic of reconciliation of inner and outer life through karma-yoga

- Aside: Is killing on the strength that the atman can’t die moral? This is not what Krishna is teaching conclusively. This passage obviously needs to be explored in tandem with what’s to come in the rest of the chapter and Gita as a whole.

Passage 4 (2.31-37): Krishna’s Teaching about the “Outer-Self,” i.e. one’s nature (svabhava) and one’s social obligation (svadharma):

- Krishna responds to Arjuna concern about sin by performing his dharma and destroying family tradition by informing him that sin is incurred by non-performance of his dharma, as well as infamy in this life and degradation in the life hereafter. He thus dismisses this argument of Arjuna as well

- This passage speaks to the social domain of being were one’s own duty (svadharma BG 2.31), coherent with one’s own nature (svabhava), is to be performed lest one incurs social degradation in this life and bad karma in the life hereafter

- This implicitly introduces the outer half of the conflict that needs reconciliation with the inner self through the teaching of karma-yoga

- The next passage represents a formal or explicit introduction to the topic of karma-yoga

After thought:

Passage three [ch 2.11-30] is one of the most famous passages referenced in the devotional communities I’ve participated in often summed up as a simple maxim, “You’re not the body.” This maxim is mostly used to discourage, implicitly or explicitly, participation in “worldly” life. What I find somewhat paradigm shifting is Krishna’s use of this passage is to encourage participation in social life, particularly the fulfillment of one’s vocation (in Arjuna’s case protecting others from harm) for the world. I suspect this would be very appealing to the postmodern temperament for social activism and sense of righteousness (i.e. spiritual-ness).

Member discussion