Demons, Monsters, Confession, & Absolution

Have you ever done something so indecorous (to be gentle about it) that you dare not speak about it even in your imagination?

If the answer is yes, you have a least one other person who shares that space with you. I’ve often wondered how the inability to vocalize my guilt and shame around unfortunate events distorts and deforms the spirit? Although its comfortable to think “not everything need be said,” intuition alerts me to something insidious in the absence of confession; a slow drip of poison that turns a monster into a demon.

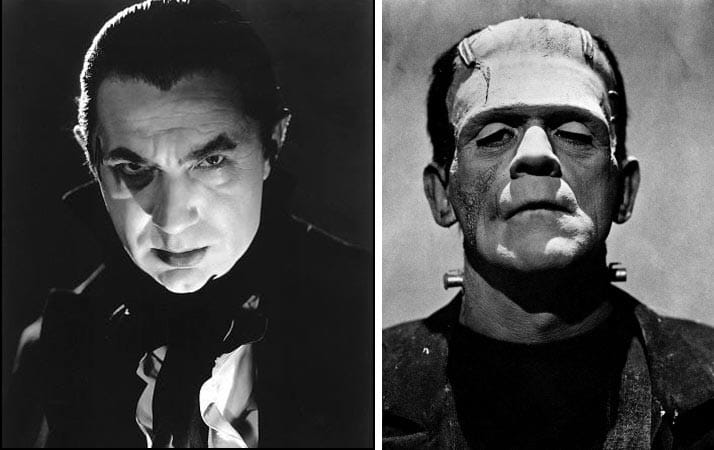

A demon is actively and purposefully evil. A monster is just weak hearted. The example of each, respectively, is Dracula and Frankenstein. Dracula is psychopathic, performing acts of evil out of pleasure. Frankenstein is clumsy. He has a desire for connection and love, but his attempts to realize these fundamental human desires, almost inexorably culminate in him causing some form of harm about which he feels guilty.

I am a monster! And if that’s hard to admit, at the very least, let it be admitted that I have the capacity for monstrosity. This can be deduced because I’ve seen and heard about the monstrous acts of other humans and I am human; and as comforting as it is to say to myself, “I would never…,” the more honest take is probably closer to, “I don’t know what it would take to push me pass the thin veneer of civility into monstrosity,” keeping in mind that (moral) weakness is as traversed a path to monstrosity as abuse of power.

But when does a monster become a demon? This may be the space where confession and absolution play a tremendous role.

In the Catholic practice of this sensitive work, one enters a confessional, a metanoia container, wherein one confesses one’s sins before a confessor, who then confers absolution upon the penitent.

“Forgive me father for I have sin. I seek to exorcise this specter from my heart before it makes me into its own image through shame. I fear to divulge the contents of my transgressions, however, for in revealing my wrongs will not love be retracted? I seek absolution, not so much in vindication from punishment or guilt, but in the consoling words ‘you are loved’ in spite of it.”

“I must exorcise this specter from my heart before it makes me into its own image through shame.” I‘ve herd the difference between guilt and shame is that in guilt the feeling is “I have done something wrong,” where as in shame, “I am something wrong.” It is through that feeling of shame, if confession is not made and absolution received, a monster may resign itself to its shame, the “I AM bad” feeling, and become a demon.

In my formative years of monastic training in nondual devotion, we would often here this process of confession ridicule and the caricature painted of the man who sins throughout the week, confesses, receives absolution only to start a new cycle of sin. The point usually intended by this caricature is that avidya—the beginningless cause of the soul’s entanglement in the birth-death cycle—is not uprooted by anything short of divine grace from heaven in the form of bhakti.

Be that as it may, the process of confession as a psychological aid to the monstrous shadow that seeks not to become a demon may be inestimable. What a great misfortune it would be to not have a single person I could trust as confessor—a friend, a parent, a mentor, a priest, a guru, or even a God—to respond with “know you are loved” after a divulgence of my wretched or even wicked acts.

Last week I vicariously experience the crippling and redemptive power of the absence and presence, respectively, of confession and subsequent absolution.

Member discussion